This week, BBC One’s Strictly Come Dancing (the U.K. version of ‘Dancing with the Stars’) began to reveal its series 13 line-up (so far we have a radio presenter, a soap star and a celebrity chef). This seems like the perfect opportunity to reflect on the historical context of the programme and highlight some of the debates that surround one of the BBC’s most successful light entertainment shows.

The U.K. television talent show originally emerged from the popular talent show programmes from the 1970s and 1980s, including New Faces (1973-1988) and Opportunity Knocks (1956-1990). These programmes showcased talent acts and relied on the studio audience to clap the loudest for their favourite act, or for viewers to send in their choices on a postcard. Strictly specifically evolved from the light entertainment format Come Dancing (1949-1988) where regional ballroom and Latin teams competed from around the country. John Fiske and John Hartley (1993) describe how the sporting structure of Come Dancing packaged the competition and hierarchy present in society in a light entertainment format, but offered neat formal resolutions in the achievement of the winners. The need for escapism and entertainment through the glitz and glamour of the competition was juxtaposed, however, against the amateur status and social reality of the contestants. So why not teach celebrities how to dance instead…

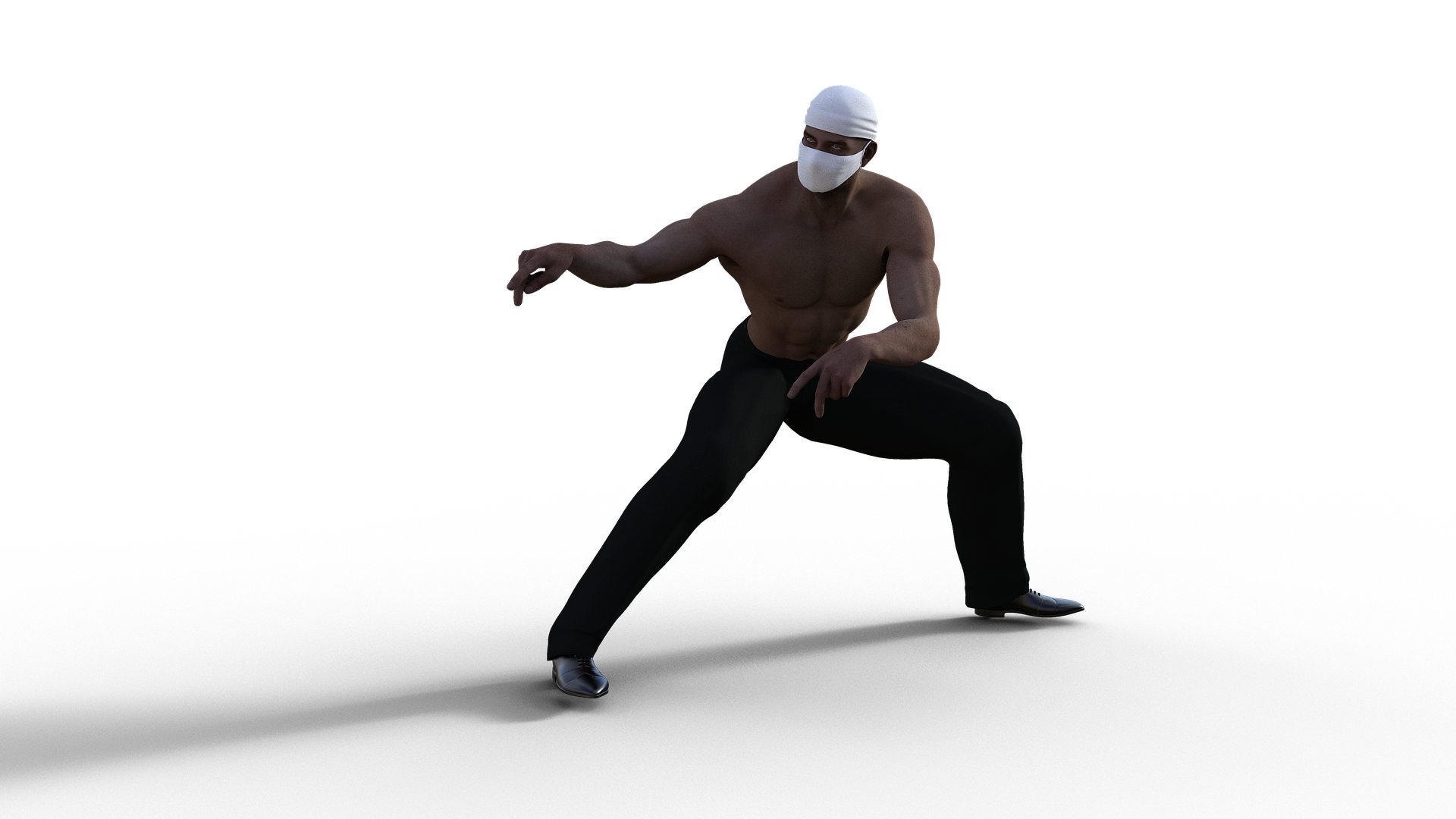

Nowadays, Strictly is lodged in the calendar as our annual dose of sequins, glamour, drama, romance, innuendo and, of course, partner dancing. The popular formula of celebrities teaming up with professional Ballroom and Latin dancers and competing on a weekly basis places the ideal of transformation at the heart of the programme (often both in terms of ability and dress size) and has been franchised worldwide under the Dancing with the Stars banner. While the judges’ mark the contestants’ ability to efficiently embody a specific corporeal technique on a weekly basis, the home viewer votes far more subjectively: who fell over, who had the most dramatic entrance, which couple is rumoured to be having an affair etc.

Two key debates have arisen before the start of this year’s broadcast. First of all, judge Craig Revel Horwood and former contestant Denise Van-Outen have called for same-sex couples to appear on Strictly within the next two years, breaking the continued heteronormative rhetoric regurgitated through the programme. Other than a single instance of a gay female sports star being paired with a heterosexual female professional dancer in in Israel’s Dancing with the Stars, the BBC will be foxtrotting into new territory. While the LGBT ballroom scene continues the flourish in U.K. cities (check out http://www.pinkjukebox.co.uk/ for LGBT classes in London), it will be interesting to see if broadcasters are ready to follow their lead.

The second debate is around the security of Strictly within the British Broadcasting Corporation. In the Conservative government’s recent green paper on the future of the BBC, it brings into question whether the broadcaster should be chasing ratings through popular entertainment formats or whether it should instead be delivering ‘quality’ programmes that are ‘unavailable on other television channels‘ (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-33584893). While the culture secretary described Strictly as admirable in its attraction of mass audiences, these comments continue to place dance on the popular screen outside of the western art canon and devalue the quality and wider cultural significance of such popular programmes. Fingers crossed that Strictly continues to ‘keeeeep dancing!’